H1N1 (Swine flu) virus

One would generally not view disease as a beautiful thing. But disease and the organisms that cause it are part of nature, and Judaism recognizes the beauty of nature. Jewish tradition provides us, for instance, with blessings to recite when we encounter natural wonders such the vastness of ocean or the colors of a rainbow. There are ones we can say upon hearing thunder or discovering a new species for the first time.

For Jews, this appreciation for nature is attributable to an awe for God’s Creation. Jews, however, do not view Creation as perfect, but rather consider humans as partners with God in making the world that God gave us an even better place. Hence, the Jewish concept of tikkun olam (repairing the world) and the answer as to why so there are so many Jewish doctors.

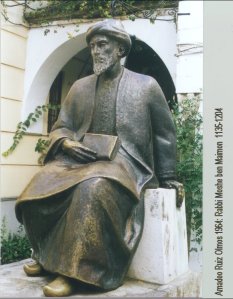

Statue of Maimonides in Cordoba, Spain

The boast of “My son, the doctor” has been heard coming in an uninterrupted stream from the mouths of Jewish mothers for millenia. Sherwin B. Nuland wrote an excellent article called, “My Son, The Doctor: The Saga of Jews and Medicine,” for The New Republic in 2005, providing a thorough explanation for this phenomenon. He explains that the fact that approximately one third of the 613 mitzvot in the Torah refer to the cleanliness of the human body and the maintenance of health led the Rabbis of the Talmud and later scholars, such as Maimonides, to conclude that the goal of the prevention and treatment of illness and the consequent prolonging of human life was to serve God.

“It was a Maimonidean precept that the purpose of keeping the body healthy is to enable the unhindered pursuit of knowledge of God, and of the perfect morality for which God is the model. The study of medicine, in sum, is a religious activity.”

Nuland went on to highlight that Jewish medicine derives from Greek medicine (and that in general, there really is no “Jewish medicine,” because Jews have always adapted their practices to the cultures in which they lived), which looked to natural science for cures. God’s having given free will to humans and enjoining us to “Choose life,” signaled to Jews that care of our bodies was up to us. No wonder, then, that there are so many Jews in the fields of medicine and scientific research.

“And so the rabbis of the Talmud taught in the presence of a heritage of ethics and with the conviction that the preservation of life is a basic teaching of their religious system of values, to be carried out by human action, existing as an instrument of divine will, yet applied independently of the divinity’s direct intervention. Though God is the ultimate healer–and indeed, in several dramatic biblical passages God chooses to intercede in order either to cause or to cure illness–God is not to be used by mankind as a medicine. When sickness occurs, a doctor is to be sought out, an imperative clearly articulated by Maimonides: ‘One who is ill has not only the right but also the duty to seek medical aid.’”

Medical professionals, whether they work in the lab or in the clinic, encounter daily the marvels of natural processes and the devastation they can wrought on the life of a human being. How exciting it is to make scientific discoveries and advances, and how painful it is to see patients suffer and die if treatment is unsuccessful. Nature is beautiful, but disease is ugly.

Conceptual artist Luke Jerram

This dichotomy is also not lost on those of us who happen not to by physicians. British conceptual artist Luke Jerram’s exploration of the tension between microbes’ devastating beauty and their devastating impact on humanity has resulted in an exhibition called “Glass Microbiology.” He, with the help of expert glassblowers, has created sculptures of viruses and bacteria of exceptionally intricate – and jarring – beauty, as is expressed in the following letter the artist received from a stranger last September:

Dear Luke,

I just saw a photo of your glass sculpture of HIV.

I can’t stop looking at it. Knowing that millions of those guys are in me, and will be a part of me for the rest of my life. Your sculpture, even as a photo, has made HIV much more real for me than any photo or illustration I’ve ever seen. It’s a very odd feeling seeing my enemy, and the eventual likely cause of my death, and finding it so beautiful.

Thank you.

Jerram’s sculptures allow us to contemplate the realities of disease, reminding us that it is a very physical presence in our world. Jerome Groopman, a doctor I very much admire, and who happens to be a practicing Conservative Jewish, has written and spoken about the relationship between medical science and religion. The two are not mutually exclusive of one another, science does not make belief in God obsolete. But, he like the hundreds of generations of Jewish doctors who have come before him, knows that in the Aleinu prayer we proclaim that our role is l’takken olam m’malchut shaddai, to repair the world in the sovereignty of God. God may be ultimately in charge, but it is our job to study nature and heal the sick:

“As much as I wish there were miracles — boom, my hand’s fixed — those are fantasies. What Judaism teaches us is the knowledge that we’re created with reservoirs of resilience. We are created with the capacity of wisdom, which means judgment — not just knowledge, but the ability to assess and weigh that knowledge to make choices. Very integral in Judaism is the sense of hope. There is capacity to improve. What it takes is drawing on gifts of science with mobilization of the spirit.” (JewishJournal.com, 2007)

© 2010 Renee Ghert-Zand. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment